(summary)

The text explores how to engage in thinking—particularly creative thinking—without becoming completely absorbed by the mind, thus maintaining awareness or “presence.” It emphasizes the importance of integrating stillness and presenceinto daily life and especially into creative practices like writing, art, or problem-solving.

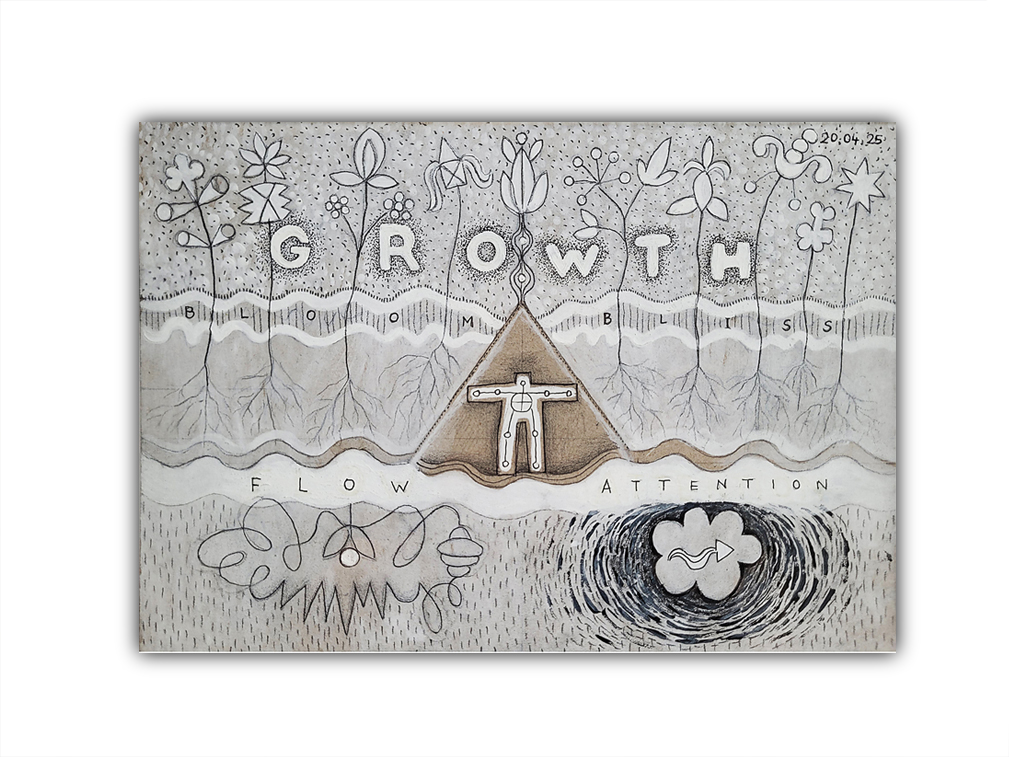

The core message is that true creativity and clarity arise when the mind is not constantly active or lost in its own momentum. To achieve this, the practice of conscious pauses throughout the day is recommended. These pauses might involve simply taking a breath, becoming aware of the inner body, or looking at the sky. These brief moments of spaciousness and stillness act as a reset, keeping one grounded and aware.

When approaching creative tasks—like writing—a similar approach is beneficial. Instead of rushing to produce results, the key is to begin with alert stillness. This doesn’t mean forcing the mind to be quiet, but rather becoming aware and attentive. From this still, alert state, one can then move into thinking. The process is dynamic: move into thinking to explore ideas, and when the thinking becomes unproductive or scattered, step back into stillness.

This alternation between thought and stillness is described as a powerful method for any kind of creative or intellectual work. The text uses the example of writing: when faced with a blank page, it’s normal to feel overwhelmed by endless possibilities. One might try writing, erase, try again—this is part of the process. But instead of pushing relentlessly, one should periodically return to a state of non-thinking. These moments of stepping back allow one to reconnect with a deeper source of creativity, beyond the accumulated knowledge of the personal mind.

A historical example given is Albert Einstein, who would often stop thinking and play the violin when his intellectual efforts reached a standstill. Playing music allowed his conceptual mind to rest, creating space for insights to arise effortlessly. Similar tools—like movement, music, or dance—can also help in stepping out of compulsive thought and back into presence.

When one practices this rhythmic interplay between thinking and stillness, a moment may arise where creative expression enters a state of flow. This flow is described as inspiration—a moment where the work seems to come through the person, rather than being created by them. Writers may find the words begin to write themselves; artists or musicians may feel they are simply channeling something greater than themselves. This creative force, referred to in the text as “Being”, is the true source of intelligence and inspiration. It is only accessible when the mind is quiet and receptive.

Many great composers and artists have echoed this experience, claiming their works felt like they were received whole, rather than consciously constructed. In these moments, the individual becomes a conduit for something beyond the personal self—a union between human consciousness and a universal intelligence.

Ultimately, the document suggests that the most profound creative work doesn’t come from the striving mind, but from the stillness behind the mind, where presence, intelligence, and inspiration originate. By learning to balance attention and spacious awareness, one can unlock this deeper creative power and remain rooted in presence while engaging in thought.